Recent History

January 1, 1906

The Natives of Australia

Birds form an important article of food in all parts of Australia, the most important being the emu, turkey, duck, pigeon, and various kinds of cockatoo.

Birds form an important article of food in all parts of Australia, the most important being the emu, turkey, duck, pigeon, and various kinds of cockatoo. Some of the methods of capturing these and other birds are sublimely simple ; in New South Wales, Angas tells us, a native would stretch himself on a rock in the sun, a piece of fish in his hand ; this would attract the attention of a bird of prey, which the black would promptly seize by the leg as soon as it tried to carry off the fish. In the same way water-fowl were taken by swimming out under water and pulling them beneath the surface, or, with a little more circumstance, by noosing them with a slender rod, the head of the fowler being covered with weeds as he swam out to his prey, which he dragged beneath the water; as soon as he had the bird in his hand he broke its neck, thrust it into his girdle, and was ready for another victim. Shags and cormorants more often rest on stakes than on the surface of the water ; accordingly, on the Lower Murray, stakes were set up for them ; the native swam out with his noose and snared them as before. During dark nights they drove shags from their resting-places, catching them as they tried to settle, and receiving in the process severe bites from the terrified birds. Almost equally simple was the method of taking black swans in West Australia. At the moulting season young men lay in ambush on the banks till the birds had got too far away from deep water to be able to swim off; then they ran round them and cut off their retreat. The West Australians would also kill a bird as it flew from its nest ; one man creeping up threw his spear so as to wound it slightly as it sat, and the other brought it down with his missile club as it flew off. Boldest of all, perhaps, is the method of taking turkey bustards in Queensland ; the fowler hangs a moth or a grasshopper, sometimes even a small bird, to the end of a rod, on which is also a noose. With a bush in front of him he creeps up to his prey, which is fascinated by the movements of the animal on the rod ; as soon as the black is near enough he slips the noose over its head and secures it. In the Boulia district pelicans are taken from ambushes ; the fowler throws shells some distance into the water, attracting the bird, which thinks the splashes are made by fish rising ; then the black pats the water with his fingers, to mimic the splashing of fish on the surface, the pelican swims round and presently falls a victim to the boomerang, or is captured by hand. The Torres Straits pigeon is taken by simply throwing any ordinary stick into the flock, as it passes down to the foreshore at no great distance from the ground ; or it may be knocked down in a more elaborate way. The flocks take the same path every night, and a high bushy tree is selected which lies in their path ; the black holds in his hands a thin switch, some fifteen feet long, which is tied to his wrist to prevent it from being accidentally dropped ; he himself is lashed to the tree to prevent accidents ; and when the pigeons come past he sweeps at them, generally bagging a fair number. On Hinchinbrook Island, the roosting-trees were known to the natives. They prepared fires beneath in the daytime ; when the pigeons had retired to rest, the fires were lighted and down came the birds. On the Tully the black observes on what trees the cockatoos roost. Then he makes fast to a suitable branch a long lawyer cane, which reaches to the ground ; at night he mounts this, holding on by his first and second toes when he moves his hands; slung round his neck he carries a long thin stick ; and with this he knocks the birds down as soon as he is within reach of them. Small cockatoos and other birds are also captured with bird-lime, which is spread not only on the branches on which they roost, but also on the young blossoms. The swamp pheasant is taken on its nest by means of a net ; in Gippsland they are taken on the nest by hand. The boomerang is a very effective weapon in a large flock of birds. Grey describes how they are knocked down with the kyli at night ; wounded birds are used as decoys ; for these birds seem to be much attached to each other. One is fastened to a tree, and its cries bring some of its companions to its aid. In Victoria and South Australia wickerwork erec- tions were made for the birds to settle on ; near them the black lay in ambush, his noose ready, and attracted his prey by imitating their calls. Emus are powerful birds, weighing perhaps 130 lbs,, and they are not so easily captured. Strong nets, sometimes fifty yards in length, are often employed to take them. The hunter notes the track by which the bird visits a water-hole, and sets up his net some thirty or forty yards behind it, the operation taking no more than five minutes ; when it returns, its flight is prevented by stationing men at possible avenues of escape, the hunters rush out and the bird is entangled in the net or knocked over with boomerangs or nulla- nullas. Sometimes an alley was built, broad at the entrance and narrowing continually, till it ended in a net ; near the opening, midway between the ends, the hunter concealed himself and imitated the call of the bird ; this he does by means of a hollow log, some two or three feet long, from which the inside core has been burnt. Holding this close to the ground over a small excavation, he makes a sort of drumming sound ; the emu struts past the men in ambush, and is easily driven into the net. Emu pits are dug, either singly or in combination ; near the feeding-grounds sometimes they are combined with a fence, opposite the openings of which they are placed, with a large central pit, in which are ambushed three or four blacks to call the birds. The emu is hunted with dogs or surrounded by the whole of a black camp ; it may also be speared by stalking it. The hunter rubs himself with earth to get rid of any smell from the body ; then with bushes in front of him and a collar-like head-dress in some parts, he makes for the bird. Young cassowaries are often run down. Ducks are often taken by stretching a long net across a river or lagoon ; the ends are fixed in the trees or on posts ; and one or more men go up-stream at a distance from the river, and then drive the birds down. At a suitable distance from the net they are frightened and caused to rise ; then a native whistles like the duck-hawk, and a piece of bark is thrown into the air to imitate the flight of the hawk ; at this the flock dips and many are caught in the net. For this mode of cap- ture four men are required. Ducks are also stalked and speared, or snared by fixed nooses set in the swamps, according to a statement of Morrell's, which, however, he leaves us to infer the kind of bird caught in this way. Flock pigeons are taken by a method unlike any described. Their habits are noted, and a small arti- ficial water-hole made in the neighbourhood of their usual drinking-place ; near this the fowler conceals himself, with a net ten or twelve feet in length laid flat on the ground close to the water ; the lower edge is fixed to the ground by means of twigs, and along the whole length of the upper edge runs a thin curved stick, the end of which the black holds in his hand ; the pigeons sit on the water like ducks ; and as soon as a favourable opportunity presents itself, the fowler, with one movement of the arm, turns the net over and bags the unsuspecting birds. For scrub turkeys a series of lawyer cane hoops are set up with connecting strips ; this is baited in the morning with nuts, fruit, etc., and about sundown he takes up his position in his ambush some twelve feet away right in front of the opening ; as soon as the turkey walks in, the black rushes out and secures it. In West Australia birds were generally cooked by plucking them and throwing them on the fire ; but when they wished to dress a bird nicely they drew it and cooked the entrails separately, parts of them being considered great delicacies. A triangle was then formed round the bird by three red-hot pieces of stick against which ashes were placed ; hot coals were stuffed inside it, and it was served full of gravy on a dish of bark. In Victoria a sort of oven was made of heated stones on which wet grass was strewn ; the birds were placed on the grass and covered with it ; more hot stones were piled on and the whole covered with earth. In this way they were half stewed. An ingenious method of cook- ing large birds was to cover them with a coating of mud and put them on the fire; the mud-pie was covered with ashes and a big fire kept up till the dish was ready ; then the mud crust was taken off, the feathers coming with it, and a juicy feast was before the hungry black. The Austrah'an is by no means uncivilised ; he appreciates high game as much as any gourmet amongst us, but he enjoys it in a somewhat different way. The Cooper's Creek aborigines collect in a bladder the fat of an exceedingly high, not to say putrid pelican, and bake it in the ashes ; then each black has a suck at the bag, the contents of which are distinctly stronger than train-oil, and what runs out of the mouth is rubbed on the face ; thus nothing is wasted.

January 2, 1906

The Natives of Australia

With the exception of the kangaroo and the opossum there are no quadrupeds which the Australian native employs largely in his cuisine.

In the hunting of animals the native can also call to his aid his skill in tracking.

Like most savages, the Australian black is keen-sighted, and he makes use of his eyes when an enemy has to be followed or an animal hunted down. Many stories are told of the extraordinary powers of the trackers. Cunningham, an early writer, says that they will say correctly how long a time has passed since the track was made ; in the case of people known to them they will even recognise the footprint as we know a person's handwriting. A tracker has been known to say that the man, unknown to him, on whose track he was, was knock-kneed, and this turned out to be correct. On one occasion a white man had been murdered, and it was suspected that he had been thrown into a certain water-hole ; before it was dragged a native, who could have had no knowledge of the affair, was called in to pronounce on the signs ; decomposition of the body had already set in, it appears, and there were slight traces of this on the surface of the pool ; the native gave a sniff and pronounced that it was 'white man's fat,' and so it turned out to be.

Grey tells a story of how he was galloping through the bush and lost his watch ; the scrub was thick and consequently the ground was unfavourable, but the watch was recovered in half an hour.

But his powers of tracking are more important to him in the search for food.

With the exception of the kangaroo and the opossum there are no quadrupeds which the Australian native employs largely in his cuisine.

The kangaroo may be taken in wet weather with dogs ; but it is more often netted in the same way that emus are taken ; sometimes three nets form three sides of a square, and beaters drive the animal in. Somewhat similar is the method of firing the bush, which is also used for other animals ; in this case the flames take the place of the net, and in their advance drive the kangaroo towards the hunters. They may also be driven, men taking the place of the fire ; or, finally, the most sporting method, they may be stalked single-handed or even walked to a standstill ; but for the latter feat extraordinary physical powers are needed. For single-handed stalking great patience is needed ; sometimes the lubra (wife) helps by giving signals by whistling; at others the hunter will throw a spear right over the kangaroo, which believes that danger threatens it from the side on which his enemy is not ; then the hunter creeps up and spears it. Grey describes how the West Australian runs down a kangaroo ; starting on its recent tracks, he follows them till he comes in sight of it ; using no concealment, he boldly heads for it and it scours away, followed by the hunter. This is repeated again and again till nightfall, when the black lights a fire and sleeps on the track ; next day the chase recommences, till human pertinacity has overcome the endurance of the quadruped and it falls a victim to its pursuer.

Before they prepare the kangaroo for cooking, the tail sinews are carefully drawn out and wrapped round the club for use in sewing cloaks, or as lashing for spears. Two methods of cooking the kangaroo were known in West Australia ; an oven might be made in the sand, and when it was well heated, the kangaroo placed in it, skin and all, and covered with ashes ; a slow fire was kept up, and when the baking was over, the kangaroo was laid on its back ; the abdomen was cut open as a preliminary and the intestines removed, leaving the gravy in the body, which was then cut up and eaten. The second method was to cut up the carcass and roast it, portion by portion. The blood was made into a sausage and eaten by the most important man present.

In Queensland the preparations are more elaborate. After the removal of the tail sinews, the limbs are dislocated to allow of their being folded over ; then the tongue is drawn out, skewered over the incisors, which are used for spokeshaves, and would be damaged if exposed to direct heat ; the intestines are removed and replaced by heated stones, the limbs drawn to the side of the body and the whole tied up in bark ; then the bundle is put in the ashes and well covered over.

In the Paroo district the kangaroo is steamed ; the oven is made of stones and wet grass, and the whole covered over with earth ; if the steam is not sufficient, holes are made and water is poured in.

The wallaby is taken with nets or in cages placed along its path. When this little kangaroo makes for shelter, it runs with its head down and consequently does not see the trap. In some districts they are trapped in pits, primarily intended to break their legs. The most ingenious method was in use in South Australia : at the end of an instrument made of long, smooth pieces of wood was fixed a hawk skin, so arranged as to simulate the living bird. Armed with this the hunter set out, and when he saw a wallaby he shook the rod and uttered the cry of a hawk ; the wallaby took refuge in the nearest bush, and the hunter stealing up, secured it with his spear.

The opossom may be hunted on moonlight nights or at any time with dogs, but the commonest method is to examine the tree trunks for recent claw marks. When these are found the native ascends the tree, cuts a hole at the spot where he believes the opossum to be, and drags the animal out. Another method is to smoke it out.

Various ways of climbing trees are known, the most ordinary being perhaps that of cutting notches for the 1 feet ; then the native ascends, usually with the ball of the big toe of each foot nearest the tree ; but in South Australia he walked up sideways, putting the little toe of his left foot in the notch and raising himself by means of the pointed end of his stick stuck into the bark. In Queensland and New South Wales the rope sling is also found ; in some cases it fits round the man's waist and he uses his axe (PI. xx.) ; in other cases one end of the vine or bark rope is twisted round his right arm, then he tries to throw the other end round the trunk of the tree ; on the end is a knot, to prevent it from slipping from his hand ; and when he has caught it, he puts his right foot against the tree, leans back and begins to walk up, throwing the kaniin a little higher at each step. If the tree is very large, he carries his axe in his mouth and cuts notches for his big toe ; the kajiiin is taken off his right arm and wound round his right thigh when the hand is wanted for cutting notches. When not in use the kamin is not rolled up, as might be imagined ; it is simply dragged through the bush by its knotted end ; it is hard and smooth. This is really the most practical method. As a rule, men only ascend trees, but in some cases women and even women carrying children have been seen by explorers to do so.

Other animals are of less importance. In the north of Australia the crocodile is taken with a noose, which a native will slip over his head, or by putting up screens in connection with a fence across a stream, in which an opening is left. The screen is made of split cane placed horizontally and all woven together with a very close mesh ; it can be rolled up like a blind.

Rats are taken in traps or knocked over with sticks ; iguanas are speared in the open or dug from their burrows ; frogs are taken in the water in flood-time or dug out; and snakes are often found in iguana burrows. The wombat and bandicoot are dug out.

October 25, 1949

Helge Ingstad

Nunamiut, Among Alaska's Inland Eskimos

A diet of tough caribou meat with practically no fat becomes dismal after a time.

It is October.

An important event is now imminent. Very soon the southward autumn migration of the caribou from the tundra to the mountains will begin. Great herds will go through the Anaktuvuk Pass during a comparatively short time. The Eskimos will then have to shoot sufficient caribou bulls, which until the mating season are very fat, to ensure our main fat requirements for the winter. Later the beasts become skinny, and without sufficient fat, people on a meat diet throughout a long, cold winter are in an awkward position.

.....

But something is. wrong. Day after day we range far over the countryside in every direction but see nothing but one or two small herds of lean bulls. A few animals are brought down, and we keep going more or less, but meals are scanty for both men and dogs.

The shortage of fat is now becoming serious. The only form of fat we have is the marrow in the bones; it is eaten raw and is a dish more delicious in times like these than words can describe. But as a caribou has only four legs and few beasts are shot, not much of this delicacy comes the way of each individual. No, a diet of tough caribou meat with practically no fat becomes dismal after a time. It is a diet which gives one the same empty feeling under the breastbone as when one has nothing to eat at all. We can eat almost unlimited quantities without feeling satisified. One's condition suffers accordingly; one feels the cold more: I have to make an effort to do things which otherwise would have been easy.

"It's rather like eating moss," Paniaq says with a smile as we attack the tough meat. And when we are out hunting together and look out from the heights over a wide area and do not see a living creature on the snow, only cold and nakedness as far as the eye can reach, he sometimes says in his dry manner: "A hungry land."

It is becoming common to borrow meat from one another. Here the Eskimos' sense of duty toward their nearest relations is clearly shown. When the hunter returns to the settlement with game, his wife immediately cuts off a few good portions of meat and gives them to her parents and parents-in-law. This diminishes the uncertainty which attaches to a single hunter's bag. In a way the community functions in hard times like a kind of mutual benevelent society.

Our situation would be more difficult if we had not a quantity of reserve provisions running about high up in the steepest mountains--the wild sheep. They are the bright spots in our existence. Leaving the lean caribou meat for the fat, tender mutton is like changing from bread and water in prison to the choicest dish at the Cafe de Paris. The sheep keep fat longer than the caribou, from the beginning of July to April.

Now and again we go out hunting sheep. But the beasts are rather scattered and in small herds, so even if we bring down some, they do not go far among sixty-five people(and 200 dogs).

....

But there was a report ahead, and I saw a ram in flight far away. There sat Paniaq, smoking his pipe beside a big ram.

We rolled and pulled the animal down to the foot of the mountain; as usual we ate the glands between the hooves and the dainty neck fat on the spot.

August 1, 1966

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories

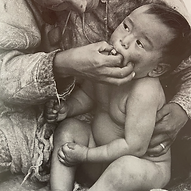

Elizabeth Arnajarnek feeds a pre-chewed morsel of caribou meat to her baby at a camp on the Barren Grounds in 1966. The Inuit gather thousands of duck eggs and eat them raw or hard-boiled. They store them for the winter.

Noises and voices drifted through the fog; the creak and groan of tide-moved ice; the honking of Canada geese; the plaintive calling of red-throated loons; the lilting song of snow buntings; the haunting, mellow woodwind crooning of courting eider drakes.

Early next morning, the fog lifted. We climbed a hill topped by an inukshuk, an ancient, roughly man-shaped Inuit stone marker, and gazed across the sea dotted with dark granite islands bathed in the golden light of dawn.

Our boats full of pots, pails, zinc and plastic wash basins, and large wooden crates, we set out to raid the holms, the rocky islets that are the eiders' favorite nesting places. Men, women, and children stumbled across the algae-slippery coastal rocks of each islet, scrambled up the sheer ice foot, and then spread, screaming with glee, across the island as dozens of eiders, sometimes hundreds, rushed and clattered off their nests. Each nest was lined with a thick, soft layer of brownish gray-flecked eiderdown and contained, on the average, four large olive eggs. The Inuit took the eggs but left the down; traditionally they dressed in furs and had no use for down. Since it was early in the season, most ducks had just laid their eggs.

We rushed from island to island and collected eggs all day, and at night we feasted on them. The children, impatient, pricked many and sucked them dry. The adults preferred them hard-boiled. They made a filling meal; each egg, in volume, equals nearly two hen's eggs, and many Inuit ate six to ten at each meal. The albumen of the hard-boiled eider egg is a smooth, gleaming white, the yolk a vivid orange. The taste is rich and rather oily.

In a week we visited dozens of islets and amassed thousands of eggs. The Inuit also shot at least a hundred ducks and several seals. It seemed amazing that these yearly raids had not decimated the ducks. But they were made so early in the season that most of the robbed ducks probably laid another clutch of eggs.

Killiktee explained to me that in earlier days a taboo forbade the Inuit to camp on eider islands. They visited the islets and took the eggs, but they camped, as we did, only on the largest islands, where few ducks nest, thus avoiding prolonged disturbances in the breeding areas. The ducks, Killiktee said, seemed just as numerous now as sixty years ago when he had first visited the Savage Islands as a boy. Polar bears sometimes swim to the islands, kill all the ducks they can, and eat the eggs. One year, Killiktee said, while the Inuit were on holms, collecting eggs, a polar bear came to camp and robbed their stores. He ate at least a thousand eggs and crushed the rest, leaving a gooey mess upon the beach. Killiktee laughed, amused and without rancor. "Happy bear!" he said.

Less lucky was a gosling caught on an islet by one of the girls. She kept it in a Danish cookie tin and tried to make a pet of it. The fluffy yellow bird peeped pathetically and, inevitably, died after a few days. The girl cried, heartbroken, over her dead pet, and then she skinned it and ate it.

All crates were full of eggs, and ducks, seals, and whale meat filled the boats. The fog rolled in again and our boats traveled through a clammy, grayish, eerie emptiness. Killiktee led, the two other boats followed closely. Dark rocks appeared for moments and vanished into the gloomy gray; ice floes loomed up abruptly. Killiktee never hesitated. "How do you know where to go?" I asked. He smiled. "I know," he said. He had traveled along this coast a long lifetime; he had seen it, memorized it, knew every current, every shoal, every danger spot. He stood in the stern like a graven image and guided our boats through the weird gray void of the fog.

In the evening he veered into a bay, a good place, he said, to catch char on the rising tide. The men set nets, the women boiled pots of meat and tea, the children played. Killiktee, tired, lay down on the shore, and moments later he was sound asleep. A dark shape upon the dark, ice-carved granite, he seemed to meld with rock and land.

Back home at Kiijuak, all eggs were carefully examined. The cracked ones we ate soon. The others were placed in large crates and stored in a cool shady cleft among the rocks. They would last the people in our camp well into the winter.

In fall, an Inuk from Lake Harbour passed our camp and took me along to Aberdeen Bay where the people quarry the jade-green soapstone for their carvings. While he had tea and talked with Killiktee, I packed and carried my things to his boat. Killiktee came to the beach. We both felt awkward. Inuit traditionally joyfully greet visitors, but visitors leave in silence and alone with none to see them off. Their language has many words of wisdom, but none for good-bye.

April 15, 1967

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories - The All-Purpose Caribou

Bruemmer explains the importance of the caribou to the Inuit and reminisces about a hunting trip he took with them. "Caribou meat was eaten fresh, or cut into strips and air-dried for future use. Fat fall caribou, often killed far from camp, were cut up and cached, food for the coming winter."

THE ALL-PURPOSE CARIBOU

Glorious it is to see

The caribou flocking down from the forests

And beginning

Their wandering to the north.

Timidly they watch

For the pitfalls of man.

Glorious it is to see

The great herds from the forests

Spreading out over plains of white.

Glorious to see.

- INUIT POEM RECORDED BY KNUD RASMUSSEN IN THE EARLY 1920s

Once they flowed like a living and life-giving tide across the tundra plains of the North. When the caribou came, an old Inuk told Knud Rasmussen in the 1920s, "the whole country is alive, and one can see neither the beginning of them nor the end - the whole earth seems to be moving.

Two animals were vital to human survival in the Arctic: seal and caribou. Seals provided food for humans and their sled dogs, strong, durable skins for boots and tents, and, above all, blubber that could be rendered into oil for the stone lamps of the Inuit, to cook their food, melt snow or ice into drinking water, dry their clothes, and warm their winter homes.

Caribou gave Inuit food and, through bones, hoofs, and antlers, a multitude of tools, toys, and weapons. Above all, from caribou skins Inuit women made the best Arctic clothing ever designed: light, durable, and so warm it made the wearer nearly impervious to any Arctic weather.

To kill caribou, Inuit used bows and arrows, lances, ambushes, traps, and a multitude of ingenious stratagems, many of them based on the hunters' knowledge of animal behavior and the quirks and weaknesses of their prey. Caribou are curious and myopic, and Inuit used these failings to get within shooting range - and that, before guns, was very close. The Inuit bow, made of pieces of driftwood, brittle and fragile, laboriously carved and pegged together, backed with plaited sinew cord to give it spring, and lashed with caribou or seal leather to give it strength, was a marvel of skill and ingenuity, but it was still a very weak weapon compared to bows of other regions where suitable wood was available. The longbow made of yew used by English archers to win the battle of Crécy in 1346 was deadly at 200 yards (180 m) and more. The Inuk bow, said Ekalun of Bathurst Inlet, who used it as a young hunter, killed only at thirty paces and less.

In 1967, I joined two Inuit hunters, Akpaleeapik and his brother Akceagok from Grise Fiord on Ellesmere Island, and their oldest sons on the last of the great polar-bear hunts made by Canadian inuie. We left the village in April and returned in June, five people, two sleds and twenty-nine dogs, and never again in my life have I known such freedom. (The diaries I kept became the basis of my first book, The Long Hunt) The rest of the world just ceased to be; time lost all meaning. We lived only for the here and now; it was a primal life, with primal joys - the endless travel through a pristine land; the great hardships of the trip; the satisfaction of being able to cope, endure, and overcome; and, although I do not hunt and never use a gun, the undeniable thrill of the hunt. And since we and our sled dogs were invariably famished after ten to twenty hours of travel every day, we looked forward with keen anticipation to our daily meal of seal or polar bear.

To hungry people every meal is a feast. A change of menu, however, is always welcome and when we crossed northern Devon Island in June and spotted caribou on a distant plain, Akeeagok / took me along to hunt them. We sledged in a valley to the edge of the plain and then we played an ancient Inuit game of deception. We advanced across the white, open plain, pretending to be a caribou: Akeeagok with arms and gun held high was the antlered torepart; I, bent at right angles, my head in the small of his back, was the rear end of the caribou. The caribou, of course, spotted us. instantly and were both curious and uneasy. Something, they realized, was not quite right. Whenever fear outweighed curiosity and they seemed ready to flee, we turned in profile to them, showing the rough outline of a caribou, and Akecagok grunted exactly like a caribou. Reassured, the caribou continued to stand and stare; once they even trotted toward us. When we were 30 yards (27 m) away, they finally panicked. But it was too late: Akeeagok shot and killed two animals. The others fled; he let them go. Both brothers were old-time hunters; they never killed more than we needed for food.

Another ruse Inuit hunters used also relied on the caribou's curiosity and shortsightedness. Two men walked past a herd. As they passed a boulder, one hid behind it and the other continued, waving, perhaps, a piece of white caribou belly skin to attract the curious animals. They followed him at a safe distance - and were shot by the hidden hunter.

In winter, Inuit cut pitfalls into drifts, covered them with thin sheets of hard Arctic snow, and baited them with urine, which caribou like for its saltiness. In spring and fall, they lay in wait with their kayaks where migrating caribou crossed rivers and lakes, and speared the swimming animals. And they built elaborate alignments of inukshuit, man-shaped cairns, on strategic ridges, which scared caribou herds toward hidden hunters. Women and children, crouched behind ridges and boulders, supplemented the line of stone men and, at a signal, rose and screamed. ("Hoo-hoo- hoo, they yelled, just like wolves," Ekalun recalled.)

Caribou meat was eaten fresh, or cut into strips and air-dried for future use. Fat fall caribou, often killed far from camp, were cut up and cached, food for the coming winter. Skins were made into clothing, bed robes, and tents.

Caribou sinew was the Inuit's thread. Plaited sinew cord was used to back the bow and give it elasticity and spring. It was used as fishing lines, and as guy lines for the tent. Depilated caribou skin was made into containers and packsacks, and covered the kayaks of inland Inuit. Toggles for dog-team harnesses were carved of caribou bone, as were the prongs of leisters (where musk-ox horn was not available), spear blades and arrowheads, and a diabolically ingenious wolf killer. Sharpened splinters of caribou shin bone were set into ice and covered with blood and fat. When a wolf came along and licked the blood, it lacerated its tongue on the frozen-in bone knife and, excited by the taste of fresh blood, licked and bled and licked and bled until it died; its skin was used for clothing.

Caribou antlers were boiled and immersed in hot water and then straightened with a qatersionfik, a big bone or palmate piece of antler into which a large hole had been worked. (Identical implements were made by reindeer hunters of the Aurignacian and Magdalenian periods in Europe, 15,000 to 30,000 years ago. Under the delusion that these were symbols of ancient authority, archaeologists have given them the grandiloquent name batons de commandment.) Straightened antler sections were scarfed, glued (with caribou blood), pegged (with pegs of caribou bone), and lashed (with strips of moist caribou skin), and made into spear shafts, tent poles, leister handles, and sled sections.

All was used, nothing was wasted. What humans did not eat, their sled dogs did. Caribou provided Inuit with food, clothing, shelter, and many tools and weapons. It was essential to life and lived in their legends and myths. The newborn Inuit baby was wiped clean with a piece of caribou fur, and when an Inuk died his shroud was made of caribou skins.

Caribou were in their thoughts and caribou marched through their dreams. In spring at Bathurst Inlet, as we waited for caribou to come to our far-northern coast, Ekalun on the sleeping platform next to me often mumbled in his sleep, and it was "tuktu, always "tuktu," endless herds of caribou, migrating through the sleeping mind of the old hunter.