Recent History

July 1, 1909

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo

Stefansson explains the game conditions of Northern Alaska and comments on the symbiotic relationship between the natives being given economic incentive to trap for furs and the traders who supplied them with food and tools.

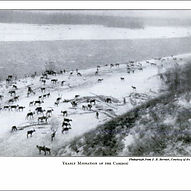

At Fort Norman game conditions have undergone great changes during the last fifty years. The mountain sheep (Ovis dalli) were then, as now, confined to the mountains west of the river, but the moose were also west of the river then, while since that time they have crossed the river and have gradually moved toward Bear Lake and encircled it until, in the summer of 1909, the first moose were seen by the Eskimo on Coronation Gulf near the mouth of the Coppermine River (a fact which, of course , was unknown to the Hudson's Bay traders and which we learned from the Eskimo in the summer of 1910) . The caribou fifty years ago were abundant around Fort Norman and used to pass on their seasonal migrations in vast herds between Fort Norman and Bear Lake; but for the last decade or two practically no caribou have been seen west of the lake, and the hunters have to go to the eastern end of it to get any. The Indians meantime have become not only few through disease, but have also lost their enterprise because of the ease with which they can make their living by sponging on the missions and the traders, and by catching a little fish in the Mackenzie; very few of them, therefore, ever go to the eastern end of the lake for caribou unless some white man goes there too. For years there had been no Indians around the mouth of the Dease River, but now that Melvill, Hornby, and Mackinlay were going in there, a number accompanied them.

Another animal the migrations of which are of interest is the musk rat. It has been spreading northeast at about the same rate as the moose . We found in 1910 that even the young men among the Eskimo of Coronation Gulf can remember the time when first they saw muskrats on the upper Dease, while today these animals are found much farther north than that, even going close down to the Arctic coast. The beaver, too, are said to be spreading northeast ward, although they are not yet so near the ocean as to be seen by the Eskimo.

We arrived at Fort Arctic Red River July 5th. This is the most northerly “ fort ” of the Hudson's Bay Company on the Mackenzie River proper. It is, perhaps, a little late in the day to explain what we should have explained in our first reference to the institu tion known as a “ fort” in the North. A Hudson's Bay " fort” is typically a small group of log cabins consisting of the factor's residence, a store in which he trades with the Indians, and possibly a small house in which he keeps dried fish or other provisions. In the early days among the Indians to the south some of the Hudson's Bay trading posts used to have stockades about them , and were, therefore, more deserving of the title of fort ; in the Mackenzie River district there is nothing to suggest special suitability for defending the trading posts against attack. In fact, there has never been any danger of attack, for a simple reason which may be worth pointing out.

In the fertile lands of the United States and Canada a saying grew up that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” because the Indian encumbered the land which the farmer needed for cultivation of crops, and the miner for his digging and delving. The Indian was in the way and had to go, for we could not let questions of mere humanitarianism and justice restrain us from taking possession of the valuable lands that the Indian had inherited from his ancestors. In the South, economic and humanitarian interests were diametrically opposed, and the economic had their way. In the North , economic and humanitarian interests happened to coincide. The northern land was valueless to the farmer, and the country was of value to the trading companies only in so far as it produced fur; and furs could best be secured by perpetuating the Indian and keeping him in possession of the lands, because dead men do not set traps. The only good Indian in the North was the live Indian who brought in fur to sell. No doubt it is largely the result of this economic fact that the Hudson's Bay Company has always treated the Indian so well that it has never been to the Indian's interest to quarrel with the Company, any more than it was to the Company's interest to quarrel with the Indian . And now that civilization , with its diseases, is making in roads into the country, and the Indian seems in danger of disappearing, it is not only human lives but also dollars and cents that the Company sees disappearing before its eyes. When they controlled all the North, they handled its problems a great deal more wisely than the Canadian government has done since, although the Canadians have been both wiser and cleaner-handed than the people of the United States. But the Company no longer own Canada, and they are powerless to check the evii tendencies which they recognize more clearly than any one else.

May 13, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 11

Eskimos are interviewed by Stefansson to learn about their religious beliefs and how magic and salvation were incompatible.

After the meal was finished we sat and talked perhaps an hour, until a messenger came it was always the children who carried mes sages) to say that my companions had gone to the house that had been built for us, and that the people hoped I would come there, too, for it was a big house, and many could sit in there at once and talk with us. On arriving home I found that, although over half the village were already there, still we had plenty of room within doors for the four or five who had come along with me to see me home. The floor of the inner half of the house had been raised into the usual two-foot-high snow sleeping-platform, covered with skins, partly ours and partly contributed by various households for our comfort; a seal-oil lamp for heating and lighting purposes had been installed. It was a cozy place, heated by the lamp to a temperature of 60° Fahr in spite of the fact that it was well ventilated by a door that was never closed day or night, and a hole in the roof that was also always open. On the bed-platform there was room for twelve or fifteen persons to sit Turkish fashion, and on the floor in front another fifteen could easily stand.

Although the house was full of guests at my home-coming, they merely stayed a few minutes, for some one suggested that we were no doubt tired and sleepy and would like to be left alone. In the morning, they said, we should have plenty of time for talking. When they were all gone, however, we did not go to sleep, but sat up fully half the night discussing the strange things we had seen. My Eskimo were considerably more excited over it all than I. It was, they said, as if we were living through a story such as the old men tell in the assembly-house when the sun is away in winter. What kindly, inoffensive- looking people these were, but no doubt they were powerful and dangerous magicians such as the stories tell about and such as my companions' fathers had known in their youth. My Mackenzie man, Tannaumirk, had, in fact , heard something to make this clear, for he had eaten supper in the house of a man who last winter had dropped his knife into a seal-hole through the ice where the sea was very deep, but so powerful was the spell he pronounced that when he reached into the water afterward the water came only to his elbow and he picked the knife off the ocean bottom. And this, Tannaumirk commented, in spite of the fact that the ice alone was at least a fathom thick and the water so deep that a stone dropped into it would no doubt take a long time to sink to the bottom.

Did they believe all this, I asked my men, though I knew what answer I would get. Of course they did. Why should I ask? Had they not often told me that their own people were able to do such things until a few years ago, when they abjured their familiar spirits on learning from the missionary of the existence of heaven and hell, and of the fact that no one can attain salvation who employs spirits to do his bidding? It was too bad that salvation and the practice of magic were incompatible ; not that such trivial things as the recovery of lost articles were of moment, but in the cure of sickness and the control of weather and ice conditions, prayers seemed so much less efficient than the old charms. Still, of course, they did not really regret the loss of the old knowledge and power, for did they not have the inestimable prospect of salvation which had been denied their forefathers through the unfortunate lateness of the coming of the missionaries? It was mere shortsightedness to regret having renounced the miraculous ability to cure disease, for God knows best when one should die, and to him who prays faithfully and never works on Sunday, death is but the entrance to a happier life.

September 13, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 13

A meeting is arranged by Stefansson between the Slavey Indians and the Eskimos

On our return journey from Bear Lake I was one morning surprised to see on the sky-line a party who evidently were not Eskimo. We hastened to intercept them, and found them to be Slavey Indians, one of whom spoke fairly good English. They had been to the northward hunting caribou, and with a vague notion that they wanted to go farther than usual on the chance of seeing Eskimo. Two days before we saw them, when they had found traces of Eskimo, they had completely lost their desire to see them. Their courage had suddenly given out, and they were now in full retreat. When they learned, however, that we had been spending several months with the Eskimo and had found them to be very friendly, the English speaking Slavey, who gave his name as Jimmie Soldat, told me that he was in the service of my friend Hornby; that Hornby had told him to keep a lookout for me, and to assist me in every way he could, and that Hornby had further requested that I take Jimmie in hand and bring him in contact with the Eskimo, so that later Jimmie might be able to guide Hornby to the place where the Eskimo are.

Now I did not desire to bring my unspoiled Coronation Gulf people into contact with civilization, with the ravages of which among the Eskimo of Alaska and the Mackenzie I am too familiar; but it seemed that the thing could not be staved off for more than a year or two, anyway, for the fact of my living with the Eskimo was already well known, and both the traders and missionaries who operate through Fort Norman would be sure to make use of the information. While I regretted the event in general, I was glad to be able to do a service, as I thought, to my friends Melvill and Hornby; so next day I took Jimmie and two of his Slavey companions to within a mile or two of an Eskimo encampment, and left them there in hiding behind a hill while I went to the Eskimo to ask their permission to bring the Indians into camp.

At first the Eskimo refused flatly. They said that they themselves had never had anything to do with the Indians; that their ancestors had had but rare contact with them, and that this contact had never been friendly; that sometimes Indians had killed some of them and sometimes they had killed some Indians, and that now no doubt these Indians had treacherous intentions in wanting to be introduced into camp. Through our long residence with them, however, Natkusiak and I had their confidence so fully that we finally talked them into allowing the Indians to come, on the condition that they leave their weapons behind them.

When I returned to Jimmie with this ultimatum, the Indians in their turn said that the intentions of the Eskimo were clear: that they intended to get them unarmed into their clutches and murder them, and Jimmie would have nothing more of the adventure. His backing out at this stage, however, did not suit me, for the Eskimo were sure to take that as a sign of treachery, and it would not have been a day until every Eskimo party in the neighborhood was on its way to the coast in a retreat in which they would have abandoned their sleds, their skins intended for clothing, and through which we would lose prestige by having brought this calamity upon them. Natkusiak and I therefore took the Indians practically by force into camp, threatening them with all sorts of dire results if they backed out. The Eskimo's reception of the Indians was friendly. The Indians were dressed in white men's clothing, and were not at all what the Eskimo had expected Indians to be like; and in fact several of them said to me at once that had they known the Indians were like this they would not have been so frightened of them.

This was early September, and the nights were dark at midnight. We had brought the Indians to camp about sundown, and an hour later, when supper had been eaten, the Eskimo invited the Indians to come and sleep in their tents; but this the Indians would not do, saying that it was their custom to sit beside the fire. This seemed to the Eskimo a strange thing, but to me it was a self- evident fib. The Indians were simply too frightened to trust themselves in the dwellings of the Eskimo. Natkusiak and I therefore sat up with the Indians for an hour or two until all the Eskimo were sound asleep, and then finally, by lying down one on either side, we got the Indians to go to sleep between us. The next morning after breakfast the Indians invited the Eskimo to accompany them down to their lodges, where they had considerable quantities of smoked caribou meat, caribou fat, and marrow-bones. Seven of the Eskimo went, including two women, and much of the forenoon was spent in the commodious lodges of the Slaveys in feasting and in exchanging opinions, in all of which I had to act as interpreter.

Finally when the feast was over and the Eskimo were apparently in the best of spirits, Jimmie brought forward a package of pictures of saints and holy men, and made a little speech in which he asked me to tell the Eskimo that he was an ambassador of a bishop of the Roman Catholic Church, and that the bishop said that if they were good men and never killed any more Indians and ab jured their heathenish practices, he would come and build a mission among them and would convert them to the true faith. This speech, which meant so much to the Indian, would of course have meant nothing to the Eskimo, for they had never heard of the good bishop or of the faith he preaches. Jimmie went on to say that he had a picture for each of them, and that if they would take them and wear them over their hearts, the pictures would protect them from all evil and be of the greatest value to them. Without translating any of these things, I took the pictures, which were the ordinary religious chromos, and gave them to the Eskimo.

It turned out that Jimmie had had no commission from Hornby, and that he had merely, from overhearing Melvill's and Hornby's conversation, found out that I was a friend of theirs, and he had used this knowledge in a confidence game of his own, the object of which was to become the first Indian who had been in friendly contact with the Eskimo, that he might thereafter pride himself on that fact, and might be able to represent himself to the bishop as having been a pioneer in the spread of the faith among the Eskimo. Apparently the results have been what he desired, for I have since heard that the Roman Catholic Church sent in missionaries at once, who arrived among the Eskimo soon after we left them, and whose work in that field will no doubt continue indefinitely.

Among other things, Jimmie told me that Melvill and Hornby were somewhere on Great Bear Lake. This was good news, and from that time I was continually on the lookout for some signs of them. Finally, on the 13th of September, it happened that the pursuit of a large band of bull caribou had taken me a long distance away from our camp, and when I finally shot three of the animals it was on a slope of a hill facing the southwest. While I was skinning them I happened to look in the direction of Bear Lake, which lay some fifteen miles distant, and there, not more than a mile away, was pitched a tepee. I took this for an Indian camp, but went up to it to make inquiries about my friends, and it turned out to be their camp. They had a day or two before heard from Jimmie about my presence in the country, and were also looking for me. They had been down on the Mackenzie River in the summer, and had some news of the outside world. King Edward was dead, and a heavier than air flying-machine had crossed the English Channel. This news, not half a year old, was fresh news indeed in that country.

February 18, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 27

When in a trance the shaman is the mouth-piece of a spirit, and at any time, by the use of the formulæ by which the spirits are controlled, he can get them to do his bidding, be it good or ill.

A shaman among the Eskimos is in his own person no wiser than you or I. In every -day life he is quite as likely to do foolish things, quite as liable to be wrong ; but when he goes into a trance his own spirit is superseded by the familiar spirit which enters his body, and it is the familiar spirit which talks through the mouth of the shaman. It is only then that his words become wisdom, on which you may rely unthinkingly. When in a trance the shaman is the mouth-piece of a spirit, and at any time, by the use of the formulæ by which the spirits are controlled, he can get them to do his bidding, be it good or ill. For that reason the shaman is deferred to, irrespective of whether you like him personally or not, and without regard to what you may think of his character and natural abilities, except that the more you fear he may be disposed to evil actions, the more careful you are not to give him offense, and to comply with everything he commands or intimates, for (being evilly disposed) he may punish you harshly if you incur his displeasure.

Just as in Rome the priests of the new religion took the place of the priests of the old, so among the Eskimo the missionary under the new dispensation takes the place of the ancient shaman of the old régime. When he speaks as a missionary, he speaks as the mouthpiece of God, exactly as the shaman was the mouth-piece of the spirits. The commands he issues at that time are the commands of God, as the commands of the shaman were not his own but those of the spirit which possessed him. And as in the old days the evilly disposed shamans were the most feared, similarly that one of all the missionaries known to me who is personally the most unpopular among his Eskimo congregation is also the one whose word is the most absolute law and whom none would cross under any circumstances. “ For,” think the Eskimo, " being a bad man, he may pray to God to make us sick or do us some harm."

April 15, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 16

The natural feelings of sympathy that had grown up through a year of association with these people, who in their way were so infinitely superior to their civilized brethren in the west, made me regret that civilization was following so close upon our heels.

Another story which we picked up at this time was that of the Imnait. These were vague and mysterious animals living in an unknown land to the west, which is also inhabited by the Kiligavait. This story did not give us nearly so much trouble in identifying it as did that of Kaplavinna, for the name of the monster was a correct reproduction of that used by my own Eskimo in the previous year in telling their adventures in mountain sheep hunting. Mountain sheep, of course, are found nowhere east of the Mackenzie River, and could not, therefore, be directly known to the Coronation Gulf Eskimo. These people were also unfamiliar with the dangers involved in the possible snow-slides and other peculiar conditions of mountain hunting. They had received from Natkusiak the general idea that mountain sheep hunting was dangerous, and being unable to ascribe any danger to the mountains as such, they had transferred the dangerousness of the snow-slides and precipices to the sheep themselves; and the hairbreadth escapes from death in snow-slides which Natkusiak had described became in their version hairbreadth escapes from the teeth and claws of the ferocious mountain sheep. The kiligavait, which they had associated with the mountain sheep in these narratives, were nothing but the mammoth, known to all branches of the Eskimo race by name at least, and known here also, according to what we were told, by the occasional finding of their bones. Of course Natkusiak had told nothing about mammoth hunting, but the mysterious mountain sheep naturally allied themselves in their minds with the also mysterious mammoth, and were therefore to be coupled together in recounting the same adventures. Thus we had a side-light, not only upon the origin of myths among primitive people, but also upon the startling rapidity with which they grow and change their form.

Along with these stories of Kaplavinna and the mountain sheep we were also told no doubt essentially truthful ones of the trading expeditions of certain men of this district to the lakes above the head of Chesterfield Inlet, as well as in all probability entirely fictitious accounts of how certain men had, during the last few years, made journeys to the moon. One of the local shamans had for a familiar spirit the spirit of a white man, and in séances spoke “ white men's language.” We were present at one of these séances; and when I said that I was unable to understand anything of what the white man's spirit said through the mouth of the woman whom he. possessed, it was considered a very surprising thing, and apparently inclined some of the people to doubt that I was really a white man as represented myself to be.

Not only does our experience here show how myths may originate, but it also shows how history and fact become mixed with fiction, and how facts are likely quickly to disappear, as in reality they do It is impossible among the Eskimo, in the absence of extraneous evidence, to rely upon anything that is said to have happened farther back than the memory of the narrator himself extends.

As we have remarked elsewhere, the mind of the Eskimo is keen with reference to their immediate environment, although of course unable to grasp things that are outside of their experience. This keenness is shown especially in the use which they make of practically everything that can be turned to account in their struggle against Arctic conditions. Wood is not especially scarce in Coronation Gulf; still, substitutes for wood have to be found now and then. We saw here a sled which illustrated remarkably the resourcefulness of the Eskimo in this matter. A man named Kaiariok, who is the son of Iglihsirk and of whom Hanbury speaks as being temporarily absent from his father's camp at the time when he visited it on Dismal Lake, found himself in the fall in need of a sled and with no wood out of which to make one. He then took a musk-ox skin, soaked it in water and folded it into the shape of a plank, pressed it flat and straight, and carried it outdoors where it could freeze. It froze as solid as any real plank, and then with his adze he went to work and hewed out of it a sled runner exactly as he would hew one out of a plank. On the upper edge of the runner he made notches for the crosspieces as he would had it been ordinary spruce, drilled holes for the lacings and put in wooden crosspieces, and made a sled which I had seen several times without discovering that it was in any way different from the ordinary wooden sleds. It was only one day when I was thinking of buying a sled that I discovered the difference. There were two sleds for sale, and I was told that one of them was better than the other because when the weather got warm it would still be useful, while the other one would flatten out and become worthless in warm weather and was therefore for sale for half the price of the first one. This cheaper sled turned out to be the musk-ox skin one, for which as an ethnological specimen I would have been willing to pay much more than the other, had there been any possibility of transferring it unchanged to a museum. There was, however, involved the same difficulty that has prevented in such places as Montreal the preservation of ice palaces from year to year.

Of all things that these Eskimo told us, the one that surprised us most was the undoubtedly true statement that a ship manned by white men and strange Eskimo was wintering in Coronation Gulf. This we felt as the reverse of good news, for the natural feelings of sympathy that had grown up through a year of association with these people, who in their way were so infinitely superior to their civilized brethren in the west, made me regret that civilization was following so close upon our heels. We had come into the country in May, and evidently this ship must have come the following September. She was wintering, they said, in the mouth of a small river about half a day's journey east of the mouth of the Coppermine. Seeing she was there, we would of course pay her a visit. We were not in particular need of assistance from anybody, but still in a far country like this one is always willing either to help or to be helped, and there was no doubt that the meeting was likely to be both pleasant and profitable to all concerned. In other words, now that the ship was there we would make the best of a situation we regretted; we would make what use of her we could and be of as much use to her as possible, although had we had our way we should have wished her on the other side of the earth.