Recent History

January 1, 1896

Air, Food, and Exercise

Babagliati establishes the dietary origin of cancer.

Page 28: “In1896 D. A. Babagliati ... published in London a small treatise on Air, Food and Exercise ... [He was] the first to establish the dietary origin of cancer, and his various books gave abundant evidence in support of his contentions.”

January 1, 1896

J.H. Romig, M.D. Letterhead

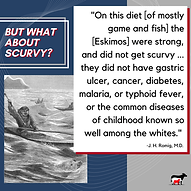

Dr Romig states that Alaskan natives on this [carnivore] diet the people were strong, and did not get scurvy ... the did not have gastric ulcer, cancer, diabetes, malaria, or typhoid fever, or the common diseases of childhood known so well among the whites.

It is written on a letterhead: “J. H. Romig, M.D., 115 East Columbia, Colorado Springs, Colo. ... 1948 ...” and signed, in ink, “J. H. Romig, M.D.” In the first part of this paper he speaks of himself in the third person:

“When Dr, J. H. Romig went to the Bering Sea region of Alaska, in the year 1896, he found the Eskimos living according to tradition, ideology, and diet, the same as they had lived for hundreds of years before.” He gives the general impression of average good health and considerable longevity. He describes their houses and housekeeping and tells that during winter most of the men spend much of their time at what whites have called club houses or bath houses, the native karrigi or kadjigi.

“The women brought the largest meal of the day to their husbands, fathers, and sons. The food was in a wooden dish ... mostly game and fish ... Dried smoked salmon was much used, and other dried fish. Seal and fish oil was much in demand and was a necessity; no one could be well without fats. Their food was cooked mostly by boiling, and was rather rare; they ate as well, especially in winter, raw frozen fish and raw meat. They kept some wild cranberries for the favored dish of akutok — made [of lean meat and] of seal or fish oil mixed with warm tallow, sprinkled with cranberries, stirred, and hardened with a little snow.

“On this diet the people were strong, and did not get scurvy ... the did not have gastric ulcer, cancer, diabetes, malaria, or typhoid fever, or the common diseases of childhood known so well among the whites. For the most part they were a happy, carefree people ...

“With the advent of gold discovery, government schools and missions, and the high price of furs, came a new era ... They were able to buy white men's food and clothing, neither of which fitted their real need. The children were sent to school and learned white man's ways ...

“These people have changed from the old way, to eating pancakes with syrup and canned goods from the store. The children have poor teeth now, as well as the older ones. They have white man's epidemics, and neither the home nor the food that once was good for them ...

“The Government is now doing much to cover up and ease these changes in native life ... It is with regret that we can see the slow passing of these once hardy people ...”

January 1, 1898

Physiological and medical observations among the Indians of southwestern United States and northern Mexico

Hrdlička observed Native Americans eating predominantly buffalo, and yet, they seemed to be spectacularly healthy and lived to a ripe old age.

"Meanwhile, the Native Americas of the Southwest were observed between 1898 and 1905 by the physician-turned-anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička, who wrote up his observations in a 460-page report for the Smithsonian Institute. The elders among the Native Americans he visited would likely have been raised on a diet of predominantly meat, mainly from buffalo, until losing their traditional way of life, yet, as Hrdlička observed, they seemed to be spectacularly healthy and lived to a ripe old age. The incidence of centenarians among these Native Americans was, according to the 1900 US Census, 224 per million men and 254 per million women, compared to only 3 and 6 per million among men and women in the white population. Although Hrdlička noted that these numbers were probably not wholly accurate, he worte that "no error could account for the extreme disproportion of centenarians observed." Among the elderly he met of age nintey and up, "not one of these was either much demented or helpless."

Hrdlička was further struck by the complete absence of chronic disease among the entire Indian population he saw. "Malignant diseases", he wrote, "if they exist at all--that they do would be difficult to doubt--must be extremely rare." He was told of "tumors" and saw several cases of the fibroid variety, but never came across a clear case of any other kind of tumor, nor any cancer. Hrdlička wrote that he saw only three cases of heart disease among more than two thousand Native Americans examined, and "not one pronounced instance" of atherosclerosis (buildup of plaque in the arteries). Varicose veins were rare. Nor did he observe cases of appendicitis, peritonitis, ulcer of the stomach, nor any "grave disease" of the liver. Although we cannot assume that meat eating was responsible for their good health and long life, it would be logical to conclued that dependence on meat in no way impaired good health."

- Nina Teicholz - The Big Fat Surprise - Page 14-15

January 1, 1898

Cancer was unknown among the Eskimos until their food was Europeanized.

In a letter of December 11, 1957, Superintendent Peacock says of his predecessor, the Reverend Paul Hettasch (who came to Labrador in 1898, thus four years ahead of Dr. Hutton) that he “was deeply interested in things medical. Although he had had but a short medical course, he was a competent doctor and surgeon (minor), a very keen observer ... He ... had little use for the Eskimo who aped the white man ... I believe that Hettasch probably predated Dr. Hutton in his statement that cancer was unknown among the Eskimos. However, the Eskimos had for some time been exposed to a white man's diet when Hettasch came to the coast, although never to the extent they were after the Hudson's Bay Company took over the trade from the Moravian Mission in 1924.” Elsewhere Peacock says that there has been since 1943 a further increase in the Europeanization of the diet, on account of certain policies of the Newfoundland government.

January 1, 1901

Cancer among Primitive Tribes

Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley never found a single true case of carcinosis while in Alaska.

Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley was born at Sandy Creek, New York, in 1879. He studied medicine from 1896 to 1900 and was graduated with the latter year's class from the medical school of Syracuse University. That year, or the next, he went to Alaska, where, after vicissitudes, he settled down to the practice of medicine at Valdez for some ten years, his last known address there being on McKinley Street. In 1927 he was associate editor of the New York City journal Cancer, under chief editor Dr. L. Duncan Bulkley. To the July issue of 1927 Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley contributed an article, “Cancer among Primitive Tribes,” in which he wrote:

“The observations, which the author of this article has used, principally ... are the result of the experiences of others ... His own personal observations on the subject were gathered during a sojourn of about twelve years among several of the different tribes of Alaskan natives, during which time he never discovered among them a single true case of carcinosis ...

“In the nearly twelve years which the writer of this article spent in Alaska, during which he came into contact with many of the different tribes of the natives living there (although not all), he never found a true case of cancer among the full-bloods and but very few among those of mixed blood. The food of these people consists almost exclusively of fish and some shell fish, with cereals, berries and some vegetables ...

“... the writer feels that the conclusion can be safely drawn that to civilization and all its influences may be attributed in a very large measure ... the increase in frequency of malignancy among primitive races.”